The Guide on How to Write a Strategy - Deep-dive Core Revenue Driver

This blog post provides is deep-dive that is intended to accompany Part 2 of this series, which, I would recommend, you read first.

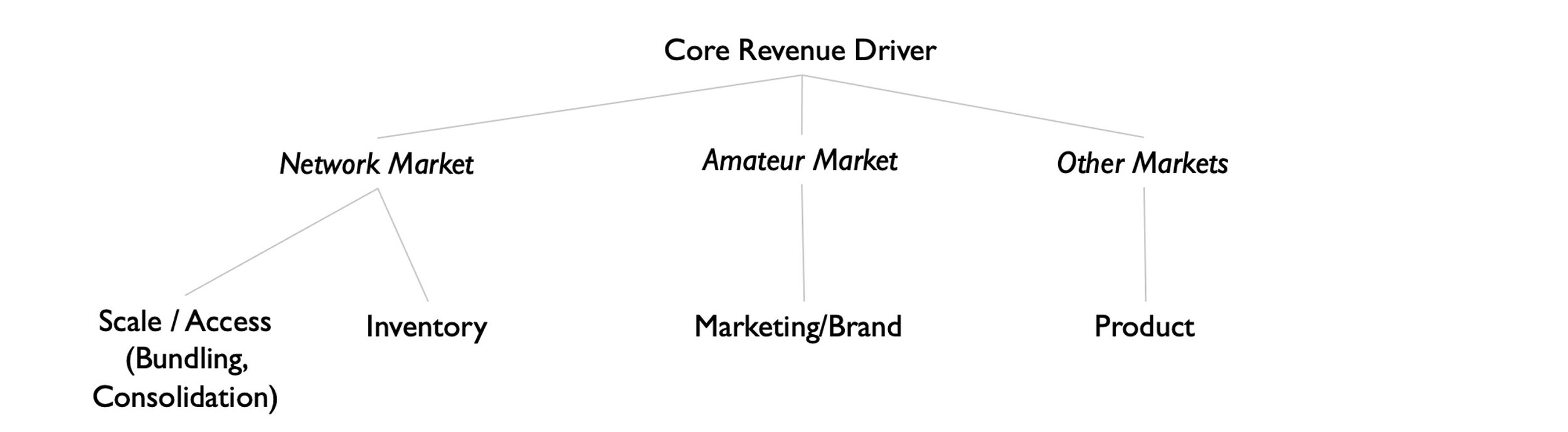

Core Revenue Driver

The core revenue driver is the underlying mechanic or psychological law of attraction that has the biggest influence on the customer’s decision on where to spend their money in the market you have chosen to be competitive in.

The first Core Revenue Driver (“CRD”) that comes to mind is of course the product itself. Having the best product (by way of its features, quality, or design) certainly has a strong influence on the customer’s decision to spend their money on it. But there are other drivers that overlay with and sometimes eclipse the product as the core driver for the customer’s decision.

These come into play particularly when (1) a market does not offer enough product differentiation potential or (2) the nature of the market favors other drivers more strongly.

Lack of product differentiation potential / Amateur Markets

Product differentiation requires two things: the potential of the product to be different from other products in the market in a meaningful way and the ability of the customer to consider these differentiating factors. And while the first one is present in most markets the latter isn’t always. At least not broadly and sufficiently enough. This is the case in markets that I call an “amateur market”. Markets in which most buyers are amateurs when it comes to evaluating the qualities of a product they want to buy.

Markets that fall in this category are -amongst others - the markets for beverages, wine & cigarettes, sneakers & sports equipment. And maybe also smartphones – but we’ll get to that later.

“What?” I hear you say, “These markets offer a lot of differentiation potential: Coke and Pepsi taste very different. Nike and Asics look very different! And I can judge that!” And you are right. You are certainly able to make out differences. However, being able to distinguish features or qualities does not mean that you can also evaluate their quality or value to you.

Blind tests have shown time and time again that Coke does not taste better than Pepsi per se. And none did it better than the “original” 2003 neuro-scientific blind-test of Baylor-College in Houston[1] in which not only taste but also the cerebral reward pathways were measured with the result that, blindly tested, Pepsi won not only in taste but also by lighting up the brains reward centers more than Coke. But Coke won both battles when the brand was revealed before the test. So the actual value or characteristics of the soft-drink-product that is Coca-Cola is not the reason for Cokes market success but the customer’s perception of it. The brand of Coca-Cola is an external value factor that supersedes the product itself. That and not the secret recipe for making Coca-Cola is the CRD of the Coca-Cola Company.

Sports equipment is a similarly geared market. Of course there are differences in design and features of bicycles, tennis rackets, golf clubs, running shoes, skis and ski boots, soccer balls etc. And I’m sure there are people in this world for whom such differences actually have meaning in terms of performance and results. But for the vast majority of buyers (including myself and I’m a most avid buyer and user of sports gear, believe me) the brand of sports equipment and often even the price-class of sports equipment does simply not make any meaningful difference that would influence the decision making of a homo economicus. And so other value factors come into play: perception, identification, belief, but also sales modalities such as availability (local vendor, club) and endorsements (Pros, coaches). All of these are more important than the qualities of the product itself.

“What about looks?” you say. Good point – this one is hard for me to prove and it’s a bit of a chicken-and-egg situation. Because its really hard to say to what degree personal taste is an autonomous aesthetic impulse vs. it being influenced by what we see others are doing. Particularly “cool” others. Let’s take something with an iconic look: a Nike Air Jordan. Do people buy this shoe because it looks the way it does (and because it does it got so popular) or do people buy the brand image of the shoe and this got it so popular and boosted its look in our perception? Does popularity follow aesthetics or do aesthetics follow popularity? Truth be told I don’t know. But I tend to think it’s the latter because the shoe would have never gotten so popular in the first place had it not been the shoe that Michael Jordan wore and it’s this history of popularity that made it a “classic” today.

TEXT

“a shoe is just a shoe until my son steps into it”

Nature of the Market / Network markets

This one is a bit of a rabbit hole and probably complex enough to write a book on its own about it. I’ll try to make it short and simplify as much as possible.

Moving over to the other big exception (at least that I can think of) to product-centric markets. I call these Network Markets. In contrast to Amateur Markets, Network Markets are business/professional markets – at least when we look at the paying customers in these markets. And the paying customer is the only customer that matters for the Core Revenue Driver because they are the only ones generating revenue.

A market qualifies as a “network market” when its biggest value is created by connecting large groups of people. One example of this is two-sided markets, where an intermediary (often referred to as a platform[2]) connects two distinct user groups in a way that provides each with the benefit of having easy access to the other.

Marketplaces fit this description squarely. But also the markets for advertising-financed products such as search and social networks are based on network effects. But out of these only marketplaces have a true two-sided network effect. Search and social create cross-group network effects only for one side: the advertisers, which benefit from having targeted access to the other group: the users. The users on the other hand have no benefit from having access/exposure to the advertisers (unless you believe giving away your data to see better-targeted ads counts as a benefit – which I don’t). Social again is a bit different in that it does create a network effect for its users – but not by providing access to the advertisers but by providing access to other users – a network effect within the same side of the market.

Regardless of these differences, all of these markets have in common:

- that the revenue comes only from the B2B side of the market - a side that benefits from the network effect - and that the users on the other side do not pay for the services that the intermediary provides to them, and

- that the most important aspect for the paying side of the market is access to the users on the other side of the market.

In essence, these markets function based on an aggressive variation of the business principle of economies of scale[3] where the old maxim of “cut price and add capacity” has been replaced with “give it away for free and add users en masse (and monetize them indirectly)”. And this mechanism has indeed proven to be one of the dominant CRDs in the digital age. Access to the user and the power to bundle content and ads on the strength of said access has replaced the distribution and production moats of the industrialization age of many markets.[4]

Again I hear you shouting: “but product is so important - Google is a much better product than Bing! And Amazon much better than eBay and Facebook blew Myspace, Friendster and Orkut out of the water because it was so much better!”. But again I’m not saying that product is irrelevant I’m merely saying that access to users is a more important driver for generating revenue. At least today. Follow me on a short trip to history lane:

Search

When the search engine Google entered the market in 1997/98 it was a vastly superior product to the incumbents such as Altavista, Hotbot, or Excite due to its innovation in search indexing. While all others generated their index based on text and keyword analysis only, Google also used weblinks to determine the quality of a search result. For the first 2-3 years, the success of Google is clearly product-driven.

But already in 2000 Google stopped having a product CRD. Because in that year Google decided to monetize its search product by way of text ads on its search pages - a somewhat surprising move given that only two years before Larry Page and Sergey Brin had published a research paper arguing that advertising-funded search was a bad idea. With this change Google’s business became 2-sided. It not only served people looking for a way to navigate the internet (“search customers”) but also people wanting to place ads on Google’s search pages (“advertisers”). And until today Google has only ever charged this second group of customers.

Accordingly, in search of the CRD, we have to shift our perspective away from the search customer to the advertiser. This makes answering the question of what Google’s CRD is a lot easier because advertisers are economically thinking professionals (at least when it comes to performance-based advertising[5] which is the only type of advertising that Google offers) whose decision-making process is easier to understand than that of a consumer.

So what are the laws of attraction for a performance advertiser? For them, only two reasons[6] exist for placing a budget[7]: reach – the number of people or “eyeballs” that can see an advertisement and return on ad spend (“ROAS”) which is the ratio of money spend for the ad and money made through the ad.[8]

Reach is simply a function of the size of Google in the search market.

ROAS is a function of the price of the ad and the amount of money to be made from a successful transaction. But mostly its a function of the conversion of the ad: how many times an ad needs to be displayed or clicked on before it leads to a money-making event for the advertiser.[9]

Conversion is dependent on two things: the capability to match a specific ad to the interests of a specific customer (“targeting” of the customer). And the quality of the customer intent at the point in time they see the ad. A customer who is already committed to buying an item is much more likely to convert when that item is displayed in an ad than a customer who is still in window-shopping mode.

Google excels at both. And the reason for that is that Google has more (relevant) data on the user than anyone else. Firstly, Google has a high-quality data-set to start with because the search keywords that the customers type in to start their internet search already give a very good insight into the specific interests of a consumer right now (“buy nike air pegasus pink”). But Google also has so many interactions with any given user that it can qualify a less precise search query (“pegasus pink”) based on the search- (and often also browsing-)history of a user. And even if the user types in something else (“weather”) Google knows that they were actively looking for a Nike Air Pegasus in Pink very recently and can cater to that. And to top it all: with all this knowledge Google usually has the first shot because most user start their internet journeys on Google.[10]

So apart from its position as a search engine in the customer journey it is Google’s access to users at scale (both in terms of the number of users and the frequency of interactions) that makes Google so dominant in reach and ROAS. Access at scale is Google’s CRD.

For the sake of completeness: Google not only dominates the advertiser side of the market with scale. It has also stopped competing on product on the user side of the market and relies on scale to keep its competition at bay. This is particularly well illustrated by the success of Google’s most important ad format in recent years, the Product Listing Ads (“PLAs”).

An example of a Product Listing Ad

The PLAs started out in 2002 under the name Froogle and became Google Product Search for some years after 2007. Today PLAs are believed to generate more than 50% of Google’s advertising revenue (which still makes up for over 75% of Google’s parent Company Alphabets total revenue). And how they became so successful has been documented by the European Commission in great detail[11]: Google’s senior management knew that the PLAs did not attract customers by virtue of their product features or quality. They would also not rank well on Google’s own search results pages. They had bad usage signals, lacked quality content and any external links. But instead of working on these flaws (they certainly had the budget), they decided in 2009 that the PLAs should simply be integrated into the Google search pages in a way that would make them a success regardless of their lackluster product quality. Google knew that the vast majority of its users always click on the top search result – after all they were conditioned that that was the best result that Google could find. And so as documented by internal emails between Google executives, it was decided that PLAs: “should trigger at the top (of the Google search results page) any time the top result is from another comparison shopping engine”. Google simply placed its own product before any competitor’s product on its search pages. PLAs only became successful because Google controlled the access to consumers.

“Bundling” is a similar practice and has become somewhat common for big tech companies: Microsoft’s integration of its Internet Explorer into Windows and Google’s integration of its search, browser, and app store into Android - just to name the ones that have been found anti-competitive by the authorities.

Social

Facebook’s/META’s success shares a lot of similarities with Google’s: Facebook too started with a unique product and later decided to monetize through advertisements. Facebook too has used its access to customers to stay ahead of the competition by copying their products and releasing these copies either on Facebook directly or otherwise funneling their users to them via Facebook: it copied Snapchat’s Stories and released them as Instagram Stories[12], it took TikToks core functionality and added it as “Reels” to Facebook and recently build Threads, a Twitter / X Clone. Building a better product has played no role here.

Marketplaces & Shops

And finally: Marketplaces. Here the CRD usually lies in the availability of demand or supply from the other side of the marketplace.

Take Amazon[13]. Their consumer eCommerce product is not great: it lacks functioning filters, it has a recommendation mechanism that is very negatively impacted by Amazon’s desire to sell Ads (paid for product placements) and it is neither particularly beautiful nor otherwise outstanding. But the inventory that Amazon offers is superb: Amazon has almost everything at a reasonable price-point and can deliver all of it consistently with short delivery times and easy returns. These qualities are inventory rather than product-related because they derive from the way that Amazon sources and handles its inventory and they can differ from inventory item to inventory item.

For third party sellers, Amazon is not a great product either. Neither is it a great partner because Amazon tends to copy very successful products and release them under their own brand (though less and less in the last years). Moreover Amazon clearly (and rightly) focuses on customer satisfaction and it uses its market power to push a lot of the cost and effort to achieve it onto the marketplace sellers - in particular for the easy returns and that customers love. They famously employ a three strikes-out rule where they will stop working with a seller if they fail customers three times. But Amazon offers so much demand that it is hard not to sell through them. And the high “tax” that Meta and Google effectively charge for traffic acquisition – over and over again as they make continuous use of their gatekeeper positions - makes Amazon’s fees and shortcomings quite digestable.

Similarly, at idealo, we were incredibly focused on product. But our CRD was never product, but inventory. We could have afforded worse of a product. But never not having the best prices. And Shops worked with us because we generated a meaningful amount of very well-converting leads – and not because we had the prettiest backend.

But this is not only true for marketplaces. It is also true for shops. The difference between the two is that shops sell their own inventory and not the inventory of their third party sellers. For customers there is no difference. And hence for Shops inventory will always be the CRD.

Other markets: product & price

Most other markets favor product as the CRD. Exceptions exist (patent trolls, market consolidators, particular distribution plays such as Tupperware or beer breweries, 2000-era incubators such as Rocket Internet) but the best product in a certain price range will often be the deciding factor for customers to decide to pay a company money.

Apple under Steve Jobs was a product company. But is it still? Bundling Product and Services does now seem part of the strategic lever of Apple - and one that shareholders particularly value. In my mind though the bundling effect is not the core driver of Apple’s revenues. The paying customer is the consumer and from a consumer perspective, the Apple ecosystem is very convenient and a good reason not to easily switch hardware but it is not the biggest magnet: a phone as good and pretty as the iPhone that runs only on third-party apps (content apps, cloud providers, email and Calendar apps, etc.) is still an attractive proposition. But a bad phone (hardware and OS) cannot be made attractive through great services alone.

What can be argued though is that brand has replaced product as a CRD for Apple. And indeed most iPhone users are amateurs with respect to the technology and technical capabilities of the phone. And within the last couple of iterations of the iPhone it was hard to detect meaningful improvements let alone killer features that would justify getting the latest model. And the same is true in comparison to other manufacturers’ handsets, although the convenience of the Apple OS certainly plays a role. So is Apple in a product or in an amateur market? I’ll leave this one up to you.

But what about price. Certainly it is one of the most common and most important qualities of a product. Rare is the market in which the decision-making process of a customer is free from price considerations. But can price be a CRD? The price of a product can be a competitive factor (price elasticity), a certain demand can be tied to a certain price range, and lowering prices can be a powerful sales tool. But despite all that I believe that price is usually only one quality of product but not a CRD in its own right. Because for most customers product value (= the value that the product has to the customer on the basis of the features, properties, image and quality) will come first[14]: a customer wants or needs something with certain properties and is prepared to pay up to limit for it. It usually does not work the other way round, where a customer is focused on a price or price range and doesn’t care as much about the product features or value. Its value for money, not money for value.

So, in summary, there are a number of markets in which a core revenue driver exists that supersedes product.

Admittedly most of the CRDs left of product in the picture above are not ideal for a startup. They either require deep pockets (scale, consolidation) or existing market power (bundling), they are risky (marketing - it is difficult to predict what your customers will want but it is even more difficult to predict what your customers will feel). And so product in a lot of cases is the early stage go-to CRD. But two notable differences exist: marketplace models – in which you have to think about inventory from day one. And any market that attracts investors who can get money at low interest rates. In the low-interest years from 2009 – 2021, growth/scaling was the number one focus for a lot of investors. It created a powerful success lever because you could get a lot more money at much better conditions and higher valuations if your strategy was one of scaling (in comparison to a company with the same product offering but more modest growth goals) which enabled you to overpower competition through your sheer focus on and speed of growth (Reid Hoffman named this “Blitzscaling”[23]). This is an example of how external factors beyond your customer’s purchase decisions can have a huge impact on your strategy.

I hope you found this trip into the rabbit hole helpful. The important takeaway here is not my categorization logic but the mere fact that product is not automatically the most important aspect of your business or strategy and that it’s worth thinking long and hard about the CRD in your market of choice first.

[1] http://www.marktforschung-mit-neuromarketing.de/seite-28.html

[2] Bill Gates favors a more narrow definition of a platform, which I like a lot: In addition to creating a network effect for its customers he requires a platform to create more economic value for them than for itself. https://semilshah.com/2015/09/17/transcript-chamath-at-strictlyvcs-insider-series/

[3] “Economies of Scale” dates back to the 60ies when Bruce Henderson, the founder of Boston Consulting Group (BCG), observed that in many businesses costs decline by a predictable amount with every doubling of cumulative volume.

[4] There are 3 forces in a supply-and-demand market: (1) production (or in the case of media: the bundling of advertising and content) (2) distribution and (3) controlling (access to) demand. In the industrial age production and distribution were the keys to power. But in the digital age, the goods are digital – information of various properties, from real-time financial data to finding like-minded people to entertaining content. Production is cheap (because there are zero multiplication costs) or even free (UGC, AI). Integration of Advertisement and content moved from the content producers to the demand controllers. And last but not least, distribution is free. Accordingly, the supply side has lost its leverage and the balance of economic power has shifted to the demand side where demand is marshaled by discovery (and not by mere distribution). And so companies that control the discovery plane have the most power in the value chain and they are the ones who are now best placed to integrate advertising, leaving everyone else in the value chain as modularized pieces without any meaningful pricing power. The exception to some degree are the owners of intellectual property that can still not be produced free or cheap because the production cost are high and/or because the artists are a scarce resource. Music (labels) and movies (studios) have therefore managed to escape the shift to some degree but not linear TV. These essays of Ben Thompson https://stratechery.com/2015/aggregation-theory/ and https://stratechery.com/2017/the-great-unbundling/ are a great read if you want to go deeper into this subject.

[5] “Classical” advertising in print, out-of-home, linear TV, cinema, etc. was never based on performance as there was no way of tracking the eyeballs that had seen an ad to a commercial event. This changed with the internet because now the ad happened in the same medium as the commercial event, making it possible to prove causality between ad spend and ad return. Accordingly, in classical advertising, you always pay for the potential of eyeballs while in performance advertising you pay for the performance of the ad – whether it’s a click on the ad (cost-per-click CPC) or a commercial success of the advertiser (cost-per-order CPO or similar).

[6] There are other factors involved as well, such as convenience of placing an ad, targeting options, creative possibilities of different ad types, the sales capabilities of publishers etc., but none of these come close to ROAS and reach.

[7] This is of course a simplification as there is not always a direct relationship between advertiser and publisher but rather there can be many layers and players in between. However, the driving factors for an advertiser will always be reach and ROAS and that is – at least in the case of search advertising – almost entirely dependent on the publisher and so I believe this simplification is acceptable.

[8] Reach and ROAS are both important as one can only partly compensate for the lack of the other: Too little reach cannot be compensated by great price – because it is simply not worth the effort for setting up, running, and optimizing a campaign – all of which require work. And great reach at a bad price may be acceptable within boundaries for well funded, fast growth companies but most companies will have to become profitable at some point, and then it’s simply a question of when your costs-of-goods-sold (“COGS”) become so high that your unit economics or contribution margin become unacceptably bad.

[9] Ok, this was a big shortcut. In more detail: ROAS is the difference between the price an advertiser has to pay for showing an ad and the amount of money that they make through a sale that was caused by that placement of the ad. In real life this is much more complex because causality and contribution are difficult to measure and hotly debated - but in principle the math done here is right. So let’s assume that one money-making event has taken place and it was 100% caused by showing the respective ad. The question is now: how much did that ad cost. The calculation of that price point is dependent on the billing model agreed between the publisher and the advertiser. Billing models in performance advertising are either CPC, or CPO/X. CPC = Cost per Click means that a fixed amount is paid when the ad gets clicked by a user. CPO/X = Cost per Order (or other agreed event) means that the advertiser pays for the conclusion of a money-making event, usually a percentage of its value. Regardless of the billing model, the conversion of the ad stipulates how much money can be generated for an advertiser from the existing ad inventory. In a CPC model, a better conversion generates more revenue for the advertiser directly increasing their ROAS. In a CPO model, the publisher extracts more value out of his ad inventory which allows him to sell the ad for less, again increasing the RAOS for the advertiser.

[10] Google can also use data to ensure that it is exploiting its advertiser budgets to the max. It knows the conversion expectations of advertisers and can calculate the value of keywords, user interactions, and clicks for the advertiser and can hence always tune their systems in a way that lets advertisers pay close to their pain threshold.

[11] Antitrust Procedure Case AT.39740 “Google Shopping”, Commission Decision C(2017) 444 final of 27.06.2017, in particular recitals (382) and (390).

[12] “…Facebook is leveraging Instagram in this way. For all of Snapchat’s explosive growth, Instagram is still more than double the size, with far more penetration across multiple demographics and international users. Rather than launch a “Stories” app without the network that is the most fundamental feature of any app built on sharing, Facebook is leveraging one of their most valuable assets: Instagram’s 500 million users.” https://stratechery.com/2016/the-audacity-of-copying-well/

[13] Amazon is not only a marketplace but also a direct seller of products that it owns but the marketplace share of paid units sold is over 60% and has better margins than amazons seller business.

[14] This research agrees https://www.firstinsight.com/blog/price-vs-quality-what-matters-most-to-consumers#:~:text=In%202021%2C%20we%20conducted%20consumer,than%20the%20price%20(30%25).

[15] https://hbr.org/2016/04/blitzscaling. Reid Hoffmann also wrote a whole book on it called “Blitzscaling: The Lightning-Fast Path to Building Massively Valuable Companies”. Seems he’s not shy on ambitious attributes.